Fowles: Father’s Day at the ballpark

Anne and R.A. Dickey in Dunedin with their children: Eli, 9; Lila, 13; Gabriel, 14; and Van, 5. Photo credit: John Lott

I oddly remember the exact moment when my dad sat me down and explained how a player’s batting average was calculated. I was just a kid at the time, my love of baseball in its very early and mostly ignorant stages. He patiently walked me through all those weird numbers next to my favourite sluggers’ names, going over simple stats in a way that was easy for a child to understand.

“So if a batter comes up to the plate ten times…”

In retrospect, my dad was probably still learning about the game himself. As a British transplant who immigrated to Canada in the late seventies—incidentally the exact same year the Blue Jays became a team—he started going to the ballpark out of an interest in his new North American home. As baseball enthralled and unfolded for him, he imparted his increasing wisdom upon me from the time I was a toddler, until I was old enough to read the rulebook for myself.

I know it’s stereotypical and cliché, but it’s nearly impossible for me to watch Father’s Day go by without thinking about how my love of baseball was nurtured by my dad. He was my very first (and still favourite) teacher and seatmate at the ballpark—beginning on Exhibition Stadium’s shiny silver bleachers, with their haphazardly spray-painted black numbers, and then at the newly minted Skydome, with its then awe-inspiring amenities (“The biggest ever video scoreboard!”) When I became an adolescent, my dad was the reason I got to see the Blue Jays through exciting playoff runs and two victorious World Series, and how I still get to brag that I was in attendance for Devon White’s legendary catch. During my angst-ridden teen years and distracted early twenties my interest in the game ebbed and flowed, but I still always enjoyed the time spent with him in the stands.

After I left home in the late nineties, the stadium became a place for us to reunite and keep each other updated on whatever was happening in our lives. “I’ll meet you in your seat,” was a common refrain, and we’d sit side by side through nine innings, just like we’d always done. Around the fifth, we’d loop the concourse together, buy a couple of hotdogs and some beers, and share stories from the months we’d been apart. The game was a way for us to stay in touch, regardless of how far away I’d roam, how infrequent the phone calls became, or how selfishly caught up I was in the minutia of my own life. It guaranteed relaxed conversation in a way nothing else did. Things were just easier there, even when life dished out its worst.

Maybe it’s unsurprising that my dad taught me a great deal of what I know about this game, but he also did so in a way that made me hungry to learn more. Never condescending or patronizing, he’d generously impart his growing understanding of all the plays and endless drama. He taught me the ground rule double, the infield fly rule, and how the umpires schedules worked. He never once pressured me to love baseball, but instead gave me the room and the education to find my own brand of interest.

At its core, baseball fandom is a community ritual in a world that is consistently lacking in human connection. So many devotees I know have beautiful stories about the relationship between their fathers, (or any kind of parental figure, really) and the ballpark. Some with more distant dads talk about the time spent there as special and sacred, while those who have lost their fathers remember days spent in the sun with nostalgia peppered with grief. New dads speak enthusiastically about introducing their kids to the game they love. They buy tiny jerseys and ballcaps, and strap their babies to their chests as they stroll the concourse, hoping their kids will find the same passion for it they do.

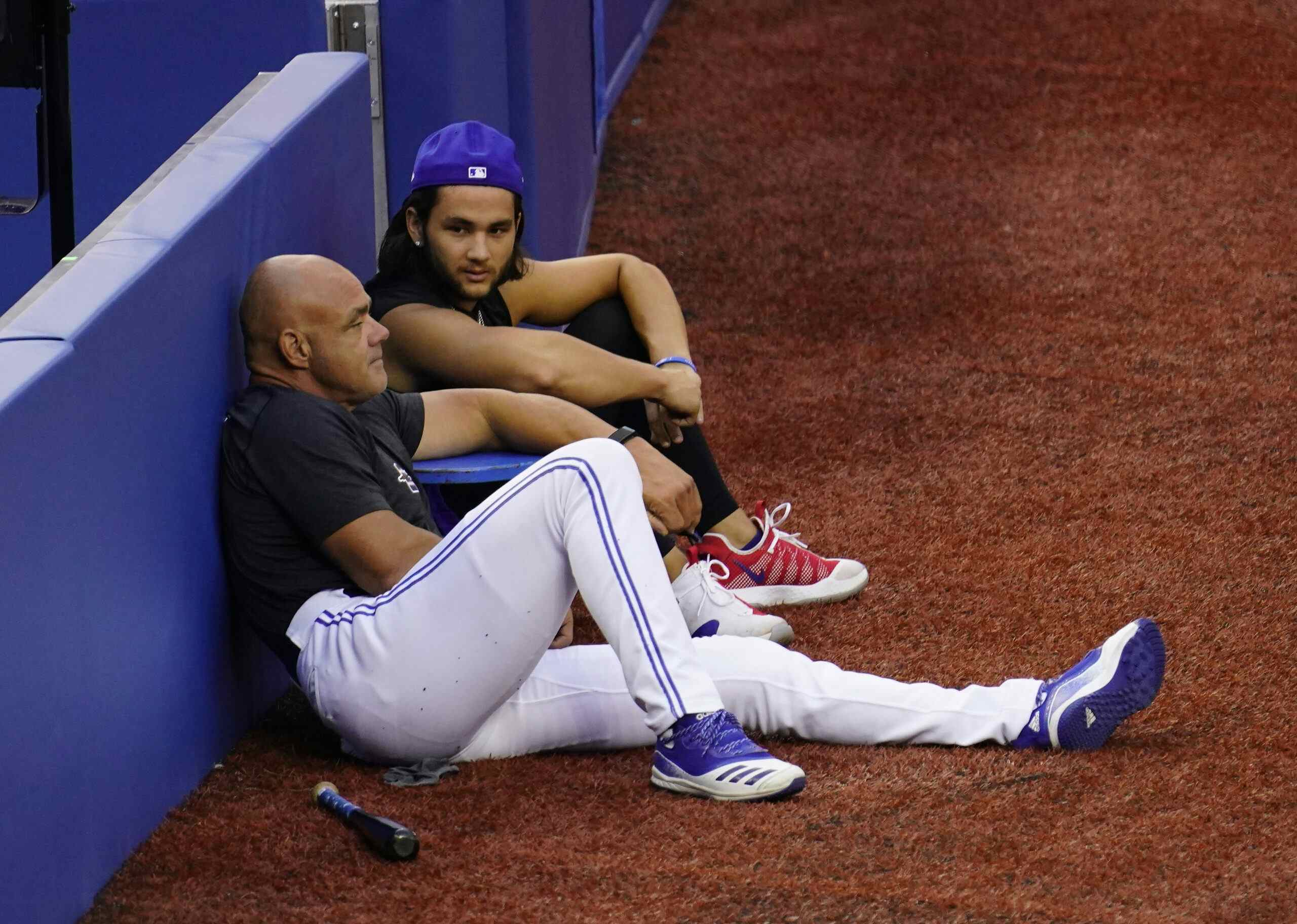

We’re also generally delighted when our favourite players are humanized by their own experiences with fatherhood. Brett Cecil taking a few days off in May for the birth of his daughter, Braelynn Natalie. (Insert the obligatory mention that the current standard MLB paternity leave is far too short.) Troy Tulowitzki getting his son’s name Taz carved on his bats. Ultimate dad-type RA Dickey talking about how much his kids have supported him, and how they’ll play a fundamental part in deciding his baseball future. With a hectic game schedule that probably doesn’t make being a dad the easiest endeavor, seeing players with their kids is a reminder that despite their hefty paycheques, hard sacrifices are definitely made.

So what exactly do you give the man who gave you the gift of baseball? More baseball it would seem. Last Tuesday, when the Jays decimated the Phillies via hot bats and a Josh Donaldson Grand Slam, my dad and I did an early version of our annual Father’s Day at the ballpark. I’m “adult” enough now that I can buy the tickets and the beers myself, and him now being retired means a noonday game is a nice, relaxing way to spend an idle afternoon. As we usually do, we reminisced about games past, about heckling Oakland A’s pitchers from above the bullpen in the 1993 ALCS, and of course about that glorious catch in game three of the 1992 World Series. We shared stories, worries, jokes, and three or so hours of quality time that baseball always delivers.

I know that when it comes to dads and baseball, I lucked out. Mine always made me feel like the ballpark was a place I deserved to be, and that I always had a right to talk about this game, long before I discovered an exclusionary sports culture that consistently told me I didn’t belong. Our phone calls now often begin with him commenting on how “my baseball team” is doing, and when I get frustrated with the sports community and the abuse it can foster, he’s there to remind me to keep pushing on.

Baseball is definitely a game that we love to pass down both to family members and friends, one that joins generations, and allows for long afternoons where seemingly disparate people can come together. A day at the park can act as a bonding exercise for many fathers, mothers, daughters, sons—whatever family you’ve chosen, or whatever family has chosen you. And when it’s at its best, it can help us relate to one another, through victories, disappointments, and a poorly belted out rendition of “Take Me Out To The Ballgame”—regardless of how different we can be.

Recent articles from Stacey May Fowles