Gavin Floyd, Steve Delabar, Their Bionic Elbows And Intertwined Journeys

By John Lott

8 years ago

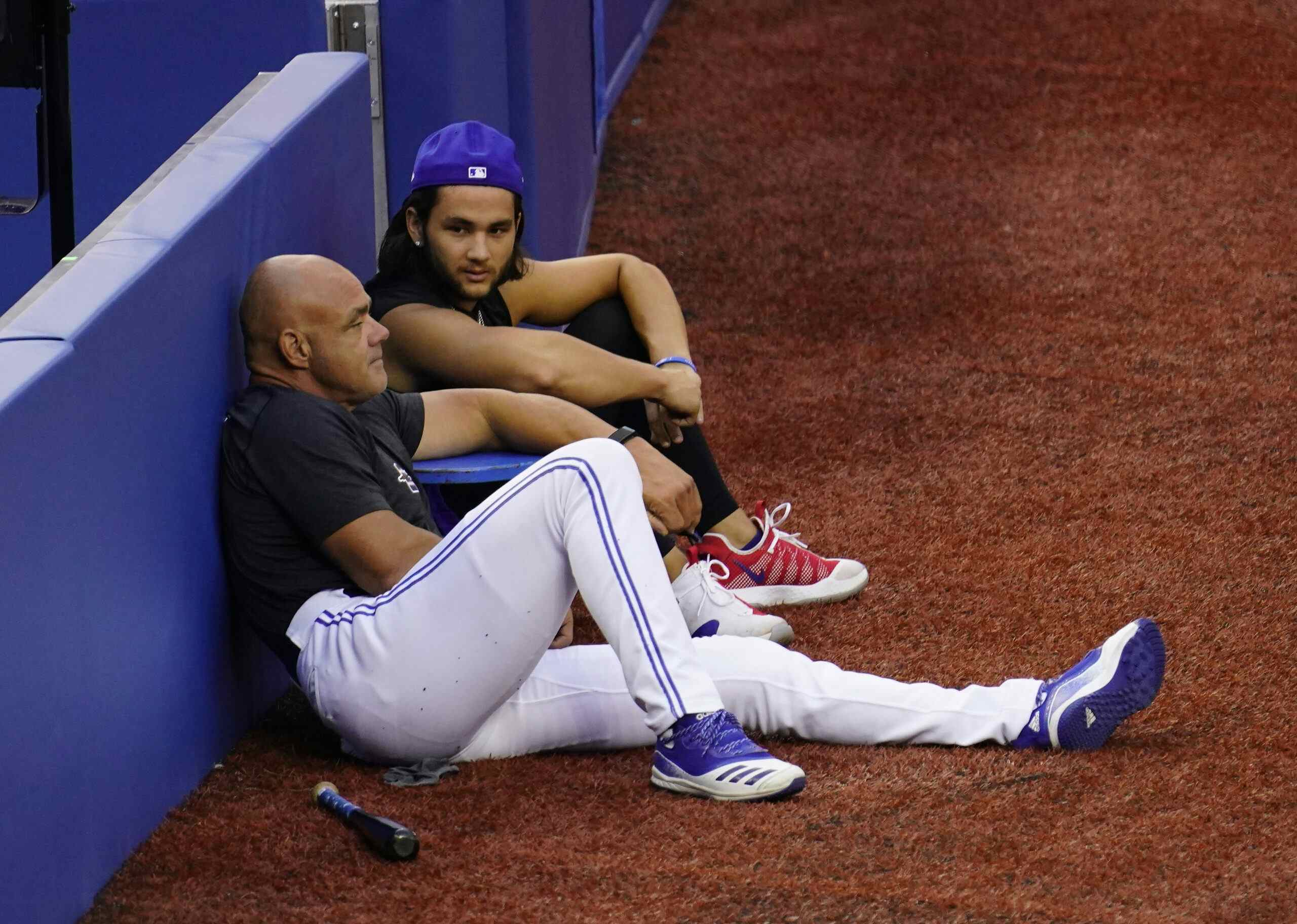

Photo Credit: John Lott

Gavin Floyd and Steve Delabar belong to an exclusive club. There was nothing funny about the admission process, although they joke about it now.

“We like to say we have more screws than any two pitchers in baseball,” Floyd says.

That would be eight screws in Floyd’s right elbow and nine in Delabar’s. There are long screws to hold the elbow bones together. There are short screws to secure a metal plate that stabilizes the joint. Floyd and Delabar need all this hardware because each broke his olecranon bone, which some people call the funny bone, but if you break yours, you won’t be laughing.

Their X-rays (this is Delabar’s) look like something from a carpentry manual. So does the surgeon’s little electric screwdriver. Its motor makes a little buzzing sound as it spins the screws into place. There are online videos that show how the operation is done. I watched one. You probably won’t want to.

Folks, especially older folks, fall and break their elbows all the time. They get them fixed and they move on. But Floyd and Delabar are baseball pitchers, so for them, the stakes are higher than for the rest of us, unless we happen to be professional arm wrestlers.

However, here they are, their screws tight, their pitches traveling over 90 miles an hour. Floyd, in particular, has been a revelation for the Toronto Blue Jays this spring after missing almost all of last season recovering from surgery to fix a second fracture in the same spot in the same elbow.

He is not pitching like a man worried about blowing out his elbow again. One reason has nothing to do with baseball (more on that later). Another reason is that a year ago, Steve Delabar helped prop him up when he was down.

“Hey,” Delabar said, “it’s just a bone. Bones heal.”

Delabar, a Blue Jay since 2012, was a bullpen candidate for this year’s team before he was released on March 29. Floyd lost out to Aaron Sanchez in the race for the final rotation job but made the team as a middle reliever. Considering the rough patch he has endured over the past three years, it is remarkable that Floyd remained a serious contender for a starting job until the very end of camp.

In 2013, he had Tommy John surgery, in which the big ligament in the elbow has to go because it’s torn. Surgeons replace it with a tendon taken from elsewhere in the body.

In June 2014, just when he was getting back to business again, Floyd threw a pitch and broke that big elbow bone.

Then in March of 2015, while in spring training with the Cleveland Indians, he broke his elbow again while throwing live batting practice.

Facing a second surgery to the same bone in the same spot, Floyd called Delabar for advice. Delabar had broken his olecranon in 2009 while pitching in independent ball. Two years later, he was in the big leagues.

Delabar said he and Floyd had a long conversation. This is the short version.

“I told him it’s a broken bone,” Delabar says. “It’s not the end of the world. Broken bones heal. Like any broken bone, you’ve got to get back to weight-bearing, and then more activity and increased workload. I guess it was kind of reassurance for him to know, ‘Hey, I’ll be able to do this again.’ ”

Floyd’s version is even shorter. “He said, ‘Oh, you’ll be fine.’ It feels solid and he hadn’t had any issues.”

And now?

“It just feels like a normal elbow,” Floyd says.

Photo Credit: John Lott

It is not a normal elbow, not with all that heavy metal in there. But it’s certainly behaving like one, pretty much as it did from 2008 through 2012, when Floyd was a fixture in the White Sox rotation. Over that span he averaged 190 innings per year, compiled a 16.3 WAR, and made close to $16-million.

When the Jays signed him Feb. 6 and gave him a million-dollar big-league contract, many fans were skeptical. Those three surgeries had confined him to 21 appearances over the past three years. Really now, what was the damage to that elbow? His last stop, which totaled seven relief appearances in September, was in Cleveland, and you know what a certain segment of Jays fans say about Cleveland. New president Mark Shapiro came from Cleveland, as did GM Ross Atkins, and the cynics smelled nepotism.

And then there was the recurring story that Gavin Floyd’s agent was Mark Shapiro’s father. Aha! That explains everything!

There was just one catch. Ron Shapiro is not Gavin Floyd’s agent and hasn’t been for seven years. Floyd’s agents are Mike Moye and Scott Sanderson.

I ask Floyd about the Ron Shapiro connection.

“I really thought he was a great person,” he says, “but I haven’t talked to him in years.”

No question about the Cleveland connection, however. Shapiro and Atkins hired Floyd to pitch there, saw what happened to his elbow and closely watched his rehab and his performance in September. They knew his medical reports inside out. They figured Floyd could be a starter again.

“Mark and Ross saw me over in Cleveland,” Floyd says. “If they weren’t there, there wouldn’t be an opportunity here. Them getting to know me over there and seeing me come back, and what I was able to do out of the bullpen despite the surgeries and rehab, I guess they felt it was a risk they were willing to take.”

***

Pitchers who need surgery often consult with others who have gone through the same thing. They want to know what’s in store. Mostly, they want to know whether they’ll be able to pitch again.

When Steve Delabar broke his elbow, there was no one to call. He had spent four-plus years in the Padres’ system and never advanced beyond Class A. So he turned to indy ball, and late in the 2009 season, shortly after taking a month off to rest a sore elbow, he came off the DL cold and threw three innings in his first game back. No bullpen sessions or live BP to ease back in. This was indy ball, and Delabar had been told that if he couldn’t pitch, he wouldn’t have a job.

After that three-inning stint, he took a day off, then pitched in back-to-back games. His team was in a playoff race. He didn’t want to let his teammates down. He could only throw fastballs because any twist or turn of his elbow caused searing pain.

Then one day he couldn’t throw a fastball anymore.

“It felt like pulling a cork out of a bottle,” he says.

Fortunately, doctors can put the cork back in this bottle. They use screws and wires and metal plates to splice the broken pieces. There is a very small sample size of pitchers who have undergone this procedure, but until Delabar was released, three were Blue Jays. The third, prospect Adonys Cardona, also broke his olecranon twice in two years. This week, in a minor-league exhibition game, he hit 97 on the radar gun and averaged 95.

But when Delabar, a right-hander, broke his elbow, he felt like a canary in a coal mine. He also took a remarkably philosophical view of his situation,

“I didn’t know if I was going to get back to the way I was before,” he tells me, “but I could at least live a normal life.”

So he went home to Kentucky and took a job as a substitute teacher. He also played slo-pitch softball, throwing left-handed. He batted left-handed too, and won a big home-run derby in Louisville.

Then, helping to coach a high school team, he started throwing right-handed again and his velocity returned. In 2011, the Mariners decided to take a chance. Delabar soared through three minor-league levels and made it to Seattle by the end of the season. The next year, he was traded to the Blue Jays. In 2013 he made the All-Star team.

It was just a bone, and it had healed.

***

Photo Credit: John Lott

Gavin Floyd’s elbow problems started with something more serious: Tommy John surgery. Breaking his elbow twice in the next two years was cruel and unusual punishment. But as tough as it was, Floyd had a lot of help as he navigated through three recoveries.

“There obviously were times when you question a lot of things. How’s this going to pan out? Am I done with baseball?” he recalls.

“For me, my relationship with God has helped me tremendously though this time – to enjoy Him, to enjoy my family, people around me, and to help me through those struggles when you worry and you fear.”

He had found religion when he was with the White Sox. It was not an epiphany, but the result of a lot of research.

He’d thought he could handle the struggles of life, and baseball, by himself. He realized all of his self-worth was wrapped up in being a baseball player, and then he started to imagine life without baseball – this was before his elbow problems – and began to ask a lot of questions. He says he realized how weak he was. His weakness led him to Christ.

“I read books by people that are experts on it, and even books by people who don’t believe that are experts on it, to hear different perspectives,” he says. “I realized I needed a saviour. I came to that surrender.”

During our interview in the Blue Jays’ clubhouse, he talks a lot about that journey to Jesus. In the background, the cacophony around a ping-pong game features some choice words you won’t hear from Gavin Floyd. The macho big-league culture is not the most fertile ground for Christianity, and many fans roll their eyes when a player thanks God for his latest round of good fortune.

I will leave such judgments to others. This works for Floyd. His evangel is soft-spoken and personal.

“Jesus is my identity,” he says with a smile. “I get joy out of reading his word. I get joy out of talking about him.”

***

After the second surgery to fix his broken elbow, Floyd’s rehab went well. But so had his first. So he worried.

“In my rehab process I eventually got to the point where I had to let it go,” he says. “And when I got to live BPs, which is when I fractured it the first time time, there was a mental hurdle there. It was a checkpoint. ‘This is where it happened last time.’ You just let it go. If it’s going to happen, it’s going to happen.”

It didn’t. By September he was pitching again, and pitching well.

I ask whether Shapiro and Atkins gave him any assurances about his role with the Blue Jays. Clearly, all three still believed he could start, but there were no guarantees, except that he would be on the team.

Our interview took place a few days before manager John Gibbons announced that Sanchez would start and Floyd would go to the bullpen. But to protect his young arm, Sanchez will not start all season. At some point, Gibbons said, Sanchez would have to go back to the bullpen and someone else would take his rotation spot. Floyd might be that someone.

He hopes so. Over a 12-year career, 196 of his 215 appearances have been starts. That’s where his heart is, and that’s what he told his bosses.

Meanwhile, he considers himself lucky. Maybe some of that luck will rub off on his new team.

“Despite the injuries, I feel like I’ve grown more in those three years of rehabbing and working on things,” he says. “To able to throw again, I feel like a kid again. I pitch in freedom. I feel like I’ve grown mechanically, mentally and spiritually, and it’s by God’s grace. I’m excited to be back. I feel like I’m better.”

Recent articles from John Lott