Lott: Estrada and Saunders honoured by All-Star consideration, but the event itself does no honour to a real baseball game

By John Lott

7 years ago

Photo Credit: John Lott

Let’s get this out of the way first. None of the following is meant to detract from the worthiness of Blue Jays Josh Donaldson, Edwin Encarnacion and Marco Estrada. They deserve their spots on the American League all-star team. Michael Saunders is also worthy; if he attracts enough fan votes for the last spot on the roster, he will join his three teammates in San Diego on July 12.

But let’s face this too: the all-star game is a gathering of elite players, rightly proud of their accomplishments, enjoying a special time together, but it is nothing like a real baseball game. Midsummer Classic? Not even close.

It is supposed to be a night of excitement for baseball fans, but TV ratings have plummeted since the 1980s. Last year’s 6.6 rating was the worst ever. (The top rating was 28.5 in 1971).

It is not hard to understand why fan interest has plummeted.

This is a made-for-TV spectacle that violates the “integrity of the game” – that hoary phrase baseball people like to cite under other circumstances. Its rules defy reason and serve as built-in impediments to playing the game “the right way,” another cliché often cited as a compliment to players of merit.

What is the appeal of an exhibition game in which the best position players play only a few innings, the best pitchers work two innings at most, the overstuffed roster consists of 34 players and managers are supposed to play as many of them as possible?

What is the attraction of a game that crams extra commercials between innings, starts late and drags well into the night, all while MLB frets about the length of its regular-season games?

Players are chosen in so many different ways that it’s hard to remember the selection path they took to get there. And absurdly, every team must be represented, so deserving players are left off the roster.

Meanwhile, as they work under those conditions, managers are also under pressure to win, because the team that wins gets home-field advantage for its league in the World Series. This is the most farcical component of all – trying to win with a 34-man roster while giving the very best players cameo appearances.

This makes playing to win, in its normal sense, virtually impossible. It is also an irrational way to determine which league starts the World Series with a home-field edge.

***

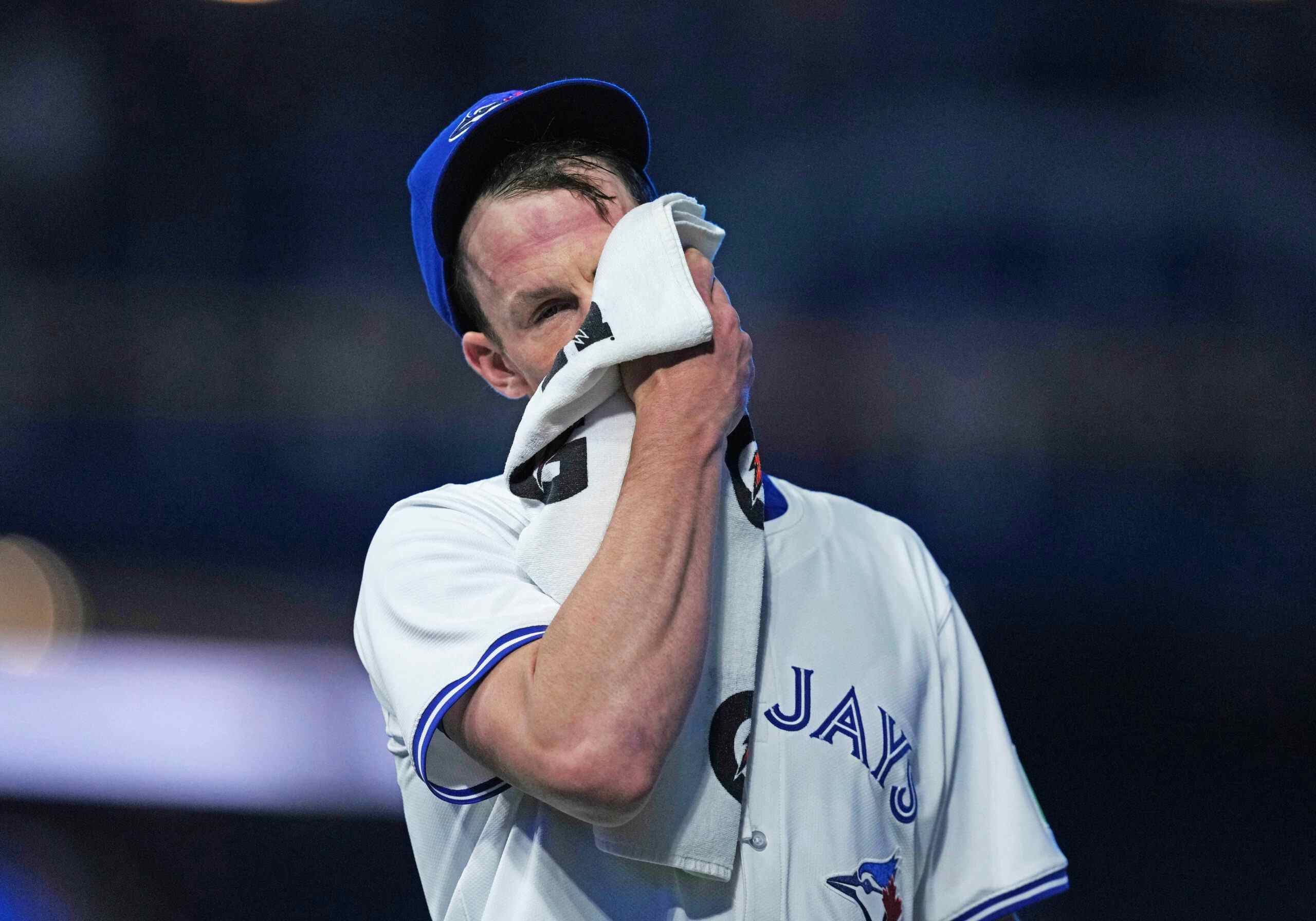

Estrada, who seemed almost an afterthought when he came to Toronto in the Adam Lind trade, has blossomed in Toronto. At the start of last season, no one would have predicted that he would develop into one of the game’s best pitchers.

And when manager John Gibbons told him the news on Tuesday afternoon, he was understandably elated. He immediately called his family.

“They were all very excited, and couldn’t be more proud, I guess,” he said. “It’s a huge honour …

“You always want to be part of an all-star team. I just wasn’t sure if I was ever going to get there. To finally get the opportunity to be one, to be an all-star, it means the world to me. It means the world to my family. They’re all extremely proud. They should be. It took a lot of hard work from everybody, not just myself.”

Saunders, who is having a career year after a knee injury ruined his 2015 season, was one of five AL players picked by the commissioner’s office for the “final vote” of fans. He said he was honoured to be considered.

Asked to elaborate on what that honour means to him, he replied: “The all-star game – just not only in baseball but in all sports – represents the top-calibre players in their sport in the world. To have my name mentioned alongside the great players that are in the all-star game is where you start saying it’s an honour. And not only this all-star game, but previous all-star games, all the way dating back to when you can remember – just the historic players, hall-of-fame players and the great players that are still playing the game today.”

***

The remarks of Estrada and Saunders pretty well sum up the modern foundations of the all-star game. It is an assembly of the best players, basking in their collective glow, deservedly sensing they have risen to a higher plane in baseball history.

It is also a gathering of another fraternity (indeed, a predominantly male clan): the continent’s baseball writers and broadcasters, virtually all of them kneeling at the altar of what MLB calls a “jewel event.”

The game is played on an otherwise fallow night for the sports media, so promoting the all-star game is a Pavlovian ritual designed to attract readers anded viewers, thereby attracting advertisers – none of which has anything to do with the virtues of the event itself.

Perhaps fan interest peaked when it did because back then there were fewer teams. Rosters were smaller. Starting pitchers often worked three innings. Star position players often played deeper into the game. Ironically, when the outcome was meaningless, managers found it easier to play to win. It was more like a real game.

Since the late 1990s, TV ratings for the all-star game have declined steadily (with a few insignificant exceptions). As MLB has tinkered with the voting process, the roster size and the TV production values, fan interest has wilted.

The all-star game does no honour to a real baseball game. Its effect on the World Series is bogus. It is an event for the players, which is fine, but less than ever an event for the fans, which is not fine at all.

Recent articles from John Lott