On Chris Colabello, Cheating, Empathy, And Making Sense Of A PED Suspension

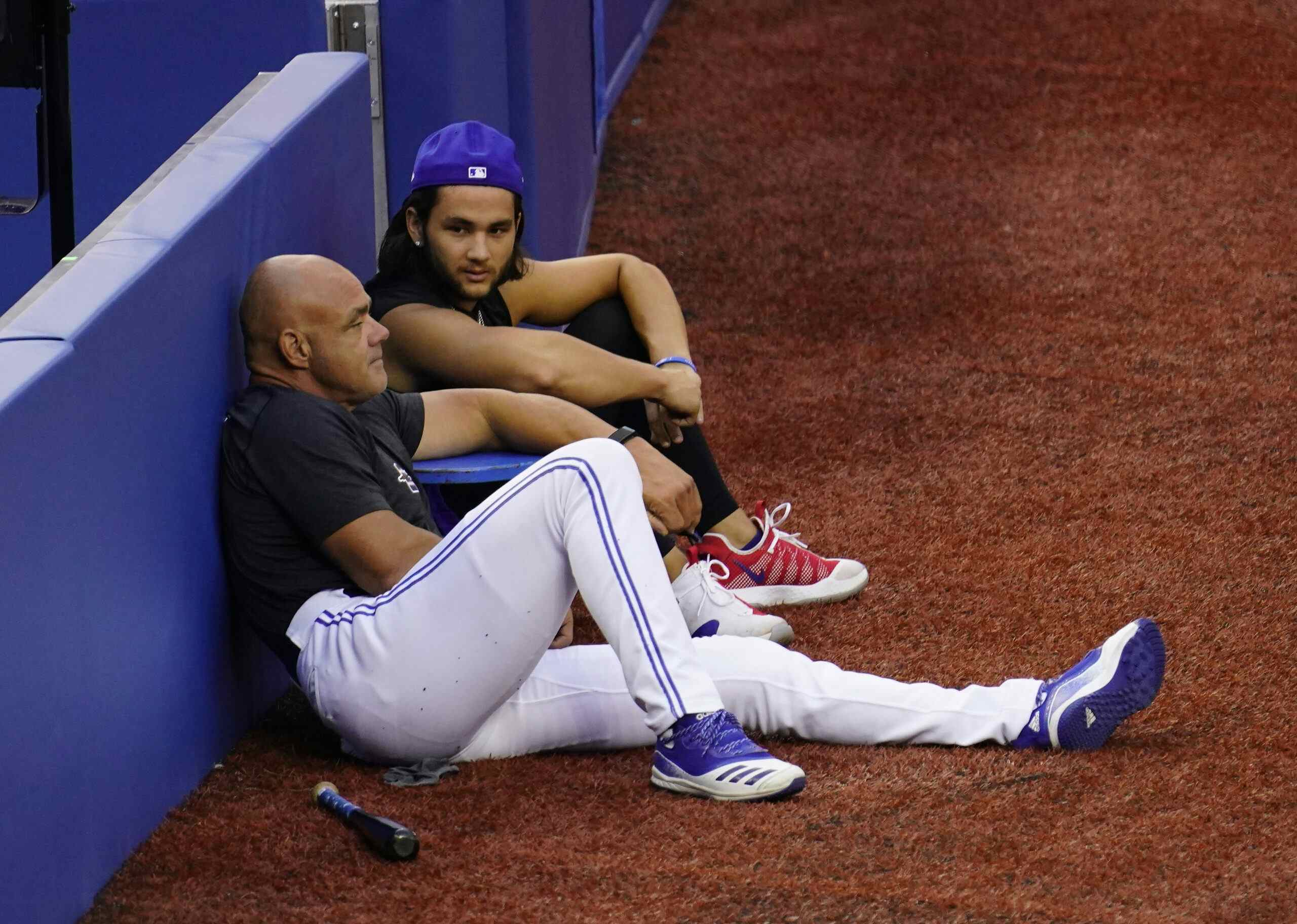

Photo Credit: Butch Dill-USA TODAY Sports

When the news broke that Chris Colabello had been suspended for eighty games after testing positive for a performance enhancing substance, someone on Twitter gently asked me if I condoned cheating.

Though the question was jarring, I can understand why it came my way. I had just extolled the many virtues of empathy and understanding, had just said that it was okay to be sad or disappointed, and reminded vitriolic Jays fans (and non-Jays fans) that baseball players are actually human beings.

“Of course not,” was my response.

Unless you are a psycho/sociopath, you likely know that cheating is wrong. It’s a fundamental life lesson learned the first time your dad catches you popping a ball into the hole at mini golf when you thought no one was looking. (Guilty, age six.) It’s a rule repeated from elementary school to university, when we’re told not to look at a classmate’s test, or lift passages from an essay, or pass someone else’s ideas off as our own. In fact, it’s generally one of the very first personal codes we are taught: cheaters are bad, greedy, selfish short-cutters, wanting to have it all without earning it, stealing the glory from those who have done the real work. It’s a pretty black and white tenant of human interaction, one intended to uphold an even playing field, and ensure that only those deserving achieve success and acclaim.

Yet, like it or not, the realm of cheating can involve all sorts of shades of grey. This doesn’t mean it should be condoned or given a pass. It doesn’t mean we should try to make excuses for it. It simply means that it’s okay to look at in context, and to endeavor to understand why it became a perceived option for an otherwise well-regarded player. Given how often PED infractions happen in the MLB, it would also seem understanding might be our best option in terms of figuring out how to prevent them.

The hard and fast rule of “cheaters are bad people” would be easy to uphold if there weren’t myriad forces at work that drive otherwise good people to make bad decisions, if we genuinely lived in a meritocracy, and if privilege didn’t exist. (As an aside, interesting that teams with bigger payroll budgets are not accused of cheating, no?) Some people cheat not out of maliciousness or selfishness, but out of pressure, fear and desperation—a need to retain their precarious accomplishments, livelihoods, or reputations. The complex reality is that each offender brings his own motivations to “taking what’s not rightfully his,” or to using nefarious means to increase his advantages.

It has always been fascinating to me that cheating is regarded as the cardinal sin of baseball. Thanks to examples like the Black Sox and the steroid era, cheating is an infraction that seems to induce more ire and league punishment than crimes that involve direct victims—see Aroldis Chapman’s thirty games for domestic violence, versus Colabello’s eighty. It’s also a detail that doesn’t lend itself well to forgiveness, and will likely haunt Colabello long after his time has been served. (In fact, TSN has already decided, “getting tangled up in PEDs could signal the death knell of his career.”)

I’ve seen A-Rod booed at enough games to understand that no one will be turning a blind eye to this, or writing the “coming back from a setback” narrative that is common with players who have committed literal crimes. The reputation of gambler Pete Rose, and MLB’s refusal to reinstate him, is further proof that cheating—even when it is implied, or doesn’t involve taking something to boost your performance—is an act destined to get you on a blacklist forever beneath the supposedly pristine reputation of The Game.

The disdain for cheating also seems to go beyond basic policies of fairness and parity, and into the psychology necessary for fan investment. When a player cheats it reminds us that baseball is more theatre than we want to believe. The act shakes our faith in the trustworthiness of what we’re watching, and makes us play back former on-field moments with a sense of betrayal. We have a hard time loving the game, and pouring our money into it, when that fantasy is tainted, meaning the common response is to make an example of the offender to reaffirm the game’s “innate goodness.”

In short, we’re naturally emotional about the news, because we feel lied to by something we care about.

Colabello testing positive for PEDs is particularly painful because so many were invested in the unique, long-haul way he rose to baseball’s stage. By making it to the minors after seven seasons in independent ball, and making his Major League debut when he was just shy of 30, he was someone fans could more easily identify with beyond the superhuman Marcus Stromans, Mike Trouts, and Bryce Harpers of the game. Instead he clings to the outskirts, representing a classic underdog story that is much easier to apply to one’s own life.

Further, Colabello is not a ego-maniacal superstar popping pills to bask in the pinnacle of false fame, glory, and excess. Instead he’s a player who (once) underscored the ideal that if you put in the effort, and were patient, you could finally achieve your goals. The fact that he did so with unsanctioned help explodes this much-needed mythology, and upends common principles that working hard enough and wanting something bad enough means you’ll get it.

In some ways I envy those with a knee-jerk response to Colabello’s infraction. For those ready to write him off, ready to scoff at his claims that he has “spent every waking moment … trying to find an answer as to why and how,” this news is not a complicated stew of feelings and dynamics that need to be reckoned with. But for me and many other fans, Colabello’s suspension is an exercise in empathy that tests our notions about him, the game, and right and wrong. It asks us to decide whether or not we should believe a player we love, and acknowledge there’s absolutely no way we can ever know the truth. The theatre of baseball is not only about that precarious state of “fairness,” but also about how little we really know about these men we voluntarily root for, day in and day out.

I don’t know Chris Colabello personally. Though everything I’ve heard about him suggests he’s a “good person,” I can’t tell you whether or not he deliberately took drugs to enhance his performance. I can’t tell you if his claim that he had no idea how this happened is believable. What I can tell you is that good people make bad choices for lots of different reasons, and that includes cheating and deception to stay in the game they love. Colabello’s prescribed identity is that he fought his way into one of the best teams in baseball, a precarious position that is likely rife with anxiety. If his decision to dope was indeed conscious, there is certainly no way it should be condoned, but I do think there’s little harm in taking the time to look at the system he exists in, and to try to grasp what might have motivated him to break baseball’s fundamental rule.

Yes, maybe Colabello has harmed “the integrity of the game.” Maybe he has shaken our faith in him. Maybe this is a kind of career death knell. But his actions are not so egregious that he doesn’t deserve forgiveness and understanding, and even the benefit of the doubt. Given everything the institution of baseball has taught us about cheating that may not be the easiest response to have, but it certainly is the most compassionate one.

Recent articles from Stacey May Fowles