Kevin Gausman, 93mph Fastball (foul) and 85mph Splitter (swinging K), Overlay.

The Similarities Between Kevin Gausman and Pedro Martinez, and thoughts on the Blue Jays’ Ace Righty

Photo credit: Dan Hamilton-USA TODAY Sports

By Tate Kispech

Aug 29, 2022, 08:00 EDTUpdated: Aug 29, 2022, 00:05 EDT

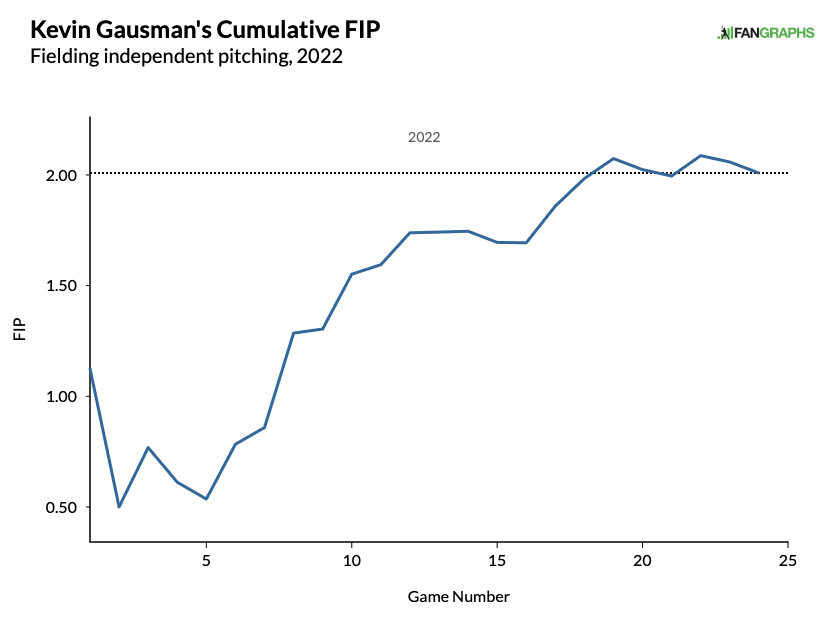

Since the turn of the century, there have only been four full seasons in which an American League starter has posted a FIP of less than 2.25…

- Pedro Martinez, 2002 (2.24 FIP)

- Pedro Martinez, 2003 (2.21 FIP)

- Pedro Martinez, 2000 (2.17 FIP)

- Kevin Gausman, 2022 (2.01 FIP)

The side note to this is that Shane Bieber technically did it too, with a 2.07 FIP in 2020. The reason that’s easily excludable though, is that Bieber only pitched 77.0 innings, and all of them were against statistically weaker Central division teams.

So, since 2000, the only American League pitchers that have been this good are Pedro Martinez and Kevin Gausman. But the similarities between the righties don’t stop there. Let’s take a closer look.

The extent to which Martinez and Gausman are similar does not start early.

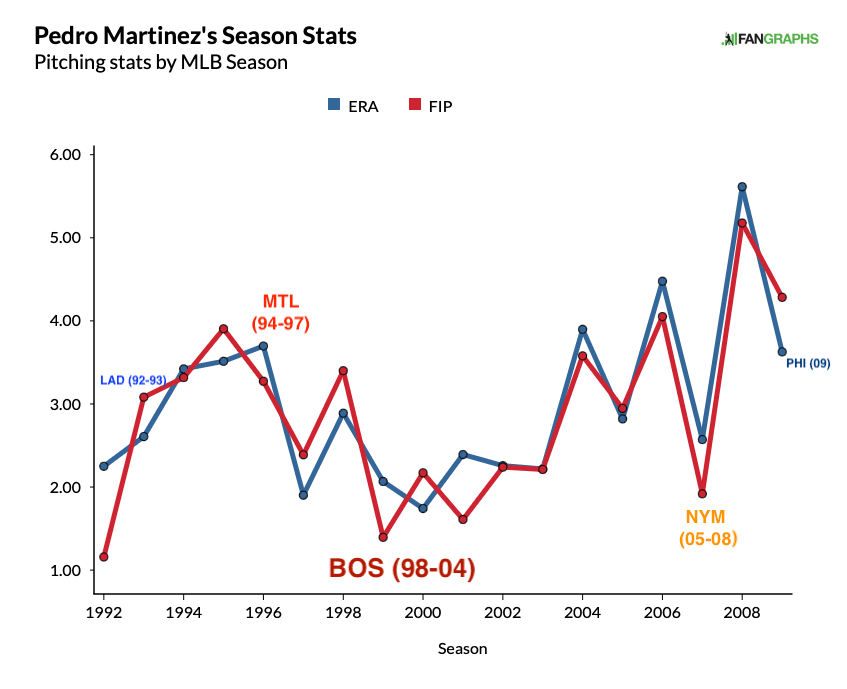

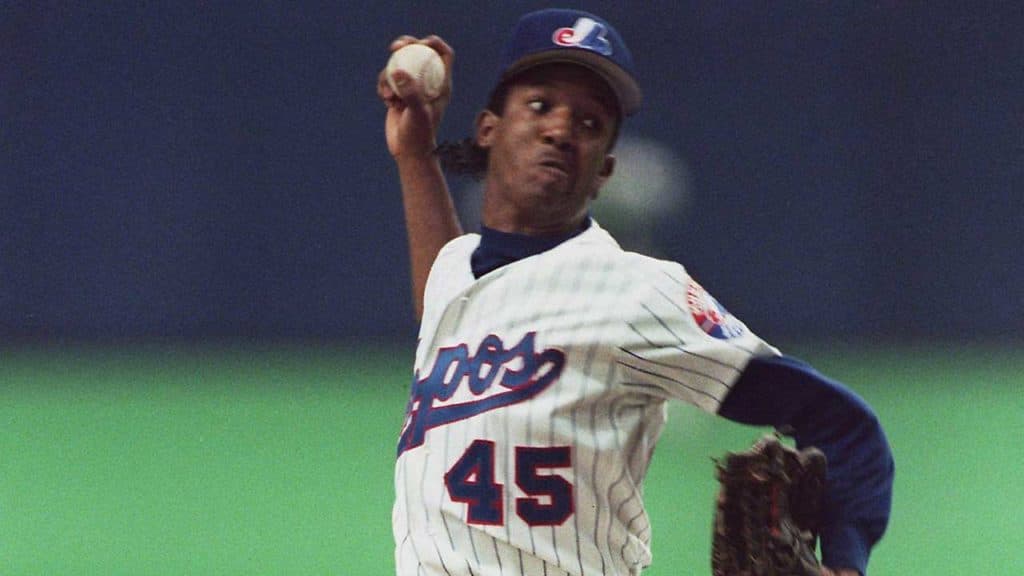

Pedro spent his first two years as a Dodger, where he didn’t often make starts, but was a great impact pitcher out of the bullpen. He only pitched 115 innings in L.A. but had a sub-3.00 ERA and FIP. After the 1993 season, the Dodgers made what has to be considered one of the worst trades in franchise history. Manager Tommy Lasorda, in need of a second baseman and not believing Pedro to be a starting pitcher, dealt the young right-hander to Montreal for the original Delino DeShields. DeShields was a very good Expo, he had recorded 11.6 fWAR and a 111 wRC+ in the four seasons prior to making his move to the City of Angels. He was, however, an okay Dodger at best. He only spent three seasons there, was a 20 percent below-average hitter, and averaged 0.9 fWAR per season.

Pedro Martinez was just a little bit better as an Expo. He averaged 5.0 fWAR per season, including a whopping 8.5 in 1997, the year in which he won his first Cy Young award.

Martinez’s time in Montreal was best described as weird. He made his way to the team in 1994, and began to pitch his first great season, posting a 3.4 fWAR before his Expos and the rest of the league went on strike. The team was 74-40 at the time. However, the team would never make the playoffs again, at least not while they played in Quebec. Martinez came back in 1995, and was good… but not as good as the prior year. In 1996, he got back to his form from two years prior, and this time was able to pitch the whole season. However, Martinez’s 5.1 fWAR only ranked 13th. He was in dire need of a breakout, to truly cement himself as one of the best starting pitchers in the sport. He got one. In 1997, Martinez absolutely dazzled. His 1.90 ERA beat out all other starters in not only his National League, but the American League too. However, he was perhaps lucky to be pitching in the NL, as Roger Clemens put up a similar ERA, more wins, and more innings pitched for a different team north of the border. Clemens also had a better FIP, but it’s not as if any sportswriters at the time would have known. Anyways, it’s a moot point, because Martinez was in the NL, a league in which he handily took home the Cy Young award. In 1998, though, he’d be sharing not only a league with Clemens, but a division. A week after winning the NL’s Cy Young award, Martinez moved to Boston.

Kevin Gausman won no such Cy Young awards in his early days, though they can also be described as weird. While Pedro was working to move from really good to elite, Gausman was only hoping to remain consistently solid. He spent his first five years in Baltimore, where he was a good but not great pitcher. In his full odd-numbered seasons with Baltimore, his ERA was above 4.20. In each even-numbered one, it was below 3.70. Gausman seemingly couldn’t make up his mind as to how good he was.

In his next two seasons, he played for three different teams. He started 2018 with Baltimore, where he was bad. He ended 2018 with Atlanta, where he was good. In the first half of 2019 with Atlanta, he was bad again. Then he moved to Cincinnati, where he was good. It was at the end of 2019 when he chose to sign with the San Francisco Giants, kickstarting his career.

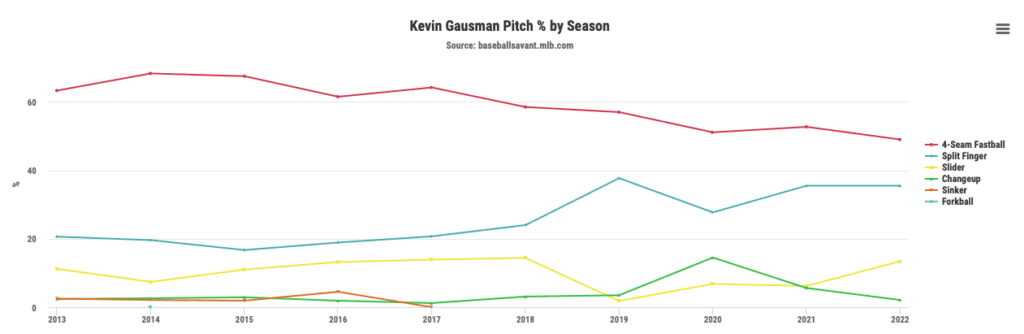

In the shortened 2020 season, Gausman was great. His ERA was 3.62, with a sub-3.10 FIP and xFIP. He owed his success, in large part, to San Francisco’s pitching coaches/directors. For years, Gausman was insistent on relying heavily on his four-seam fastball, which was pretty unobjectionably a bad pitch. In 2019, it was hit hard more than any other pitch of his, while also generating fewer whiffs than any other weapon in his arsenal. Finally, in 2020, he dropped his FF usage by six percent, and success followed.

ERA- and FIP- take the ERA and FIP of a pitcher, then adjust for run environment. 100 is league average, and lower is better. Gausman’s 83 ERA- and 73 FIP- in 2020 were both the best marks of his career up until that point. Then, in 2021, Kevin got better. His FIP- was worse by one percent, but his ERA- improved by 14 percent. When you pair that with 192 innings pitched, Gausman ranked 6th in the NL in fWAR, and finished in the same place in Cy Young voting.

As a side note, Gausman and Martinez were both similar in the fact that both of them often bounced between the bullpen and the rotation in their early years. In Gausman’s breakout 2020, he pitched one scoreless inning against the Padres to end his season. This was because the Giants needed to win the game in order to make the playoffs. They lost. To date, that’s the last relief appearance Gausman made in his career. Barring any situations similar to the one that ended his 2020 season, it’ll also be the last regular season relief appearance that he’ll ever make. For Pedro Martinez, that final relief appearance wouldn’t come until he was finishing off one of the greatest seasons in the history of the sport.

It is impossible for me to sit here and come up with adequate superlatives to describe how good Pedro Martinez was in 1999. Nobody’s EVER recorded more single-season fWAR as a pitcher, and the only player or pitcher with more fWAR since integration was Bonds, who’s probably the only one with a good argument against Martinez.

We talked about FIP- in relation to Gausman earlier. When it comes to Martinez, nobody who’s ever pitched 150 innings in a season has had a mark better than his 31 FIP- in 1999. Corbin Burnes came closest in 2021, as he finished at 38. The rest of the field isn’t even close. Martinez’s 1999 was 14 points better than Randy Johnson’s 1995, the 3rd best mark ever. That’s the same difference between Randy’s ’95 and Bert Blyleven’s ’73, the 45th best season of all time by FIP-. The season prior to Y2K was also the 10th greatest year of all time by ERA-, the third best by K%, and the second best by K-BB%. He then followed it up in 2000 with the second greatest pitching season in baseball history. I can say all of the same things about 2000 as I did about 1999, but let me save you the adjectives and instead give you the numbers.

- 35 ERA- (best ever)

- 48 FIP- (tied 5th best ever)

- 0.74 WHIP (best ever)

- 34.8% K% (10th best ever)

- 30.8 K-BB% (5th best ever)

- .166 BAA (best ever)

- 11.7 bWAR (5th best ever among post-integration pitchers)

- 9.4 fWAR (15th best ever among post-integration pitchers)

Pedro Martinez was really good. His changeup was great. It’s widely accepted as the greatest pitch of its type ever. It is sad that no statistician or fan will be ever able to view pitch data for that changeup, because it just wasn’t tracked at the time. The best I can give you is eyewitness accounts of just how good the pitch was.

The Boston Globe has a great little piece on Pedro’s career, with some really fun visualizations of Martinez in a Sox jersey. The article states that “Martinez threw the [changeup] with the same arm speed and arm slot as the fastball…and [it would] end up closer to the ground than the strike zone.” Or, instead of just reading, you can watch poetry in motion for one minute and 38 seconds…

Interestingly enough, it took Pedro about 1100 Major League innings before he put it all together and had two of the best-pitched seasons ever. It took Kevin Gausman about 1100 Major League innings until he got to 2022. He’s now having the 8th best post-integration season by FIP-. He’s doing it on the back of, in Pedro Martinez fashion, one of the best-offspeed pitches in the league. So, that’s enough about Pedro for now. Let’s take a closer look at Kevin Gausman.

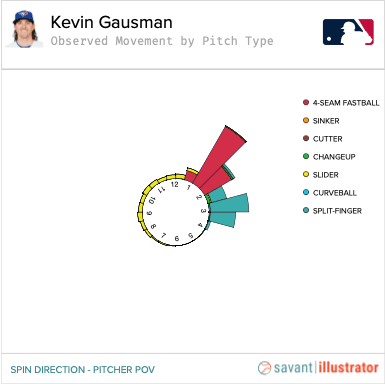

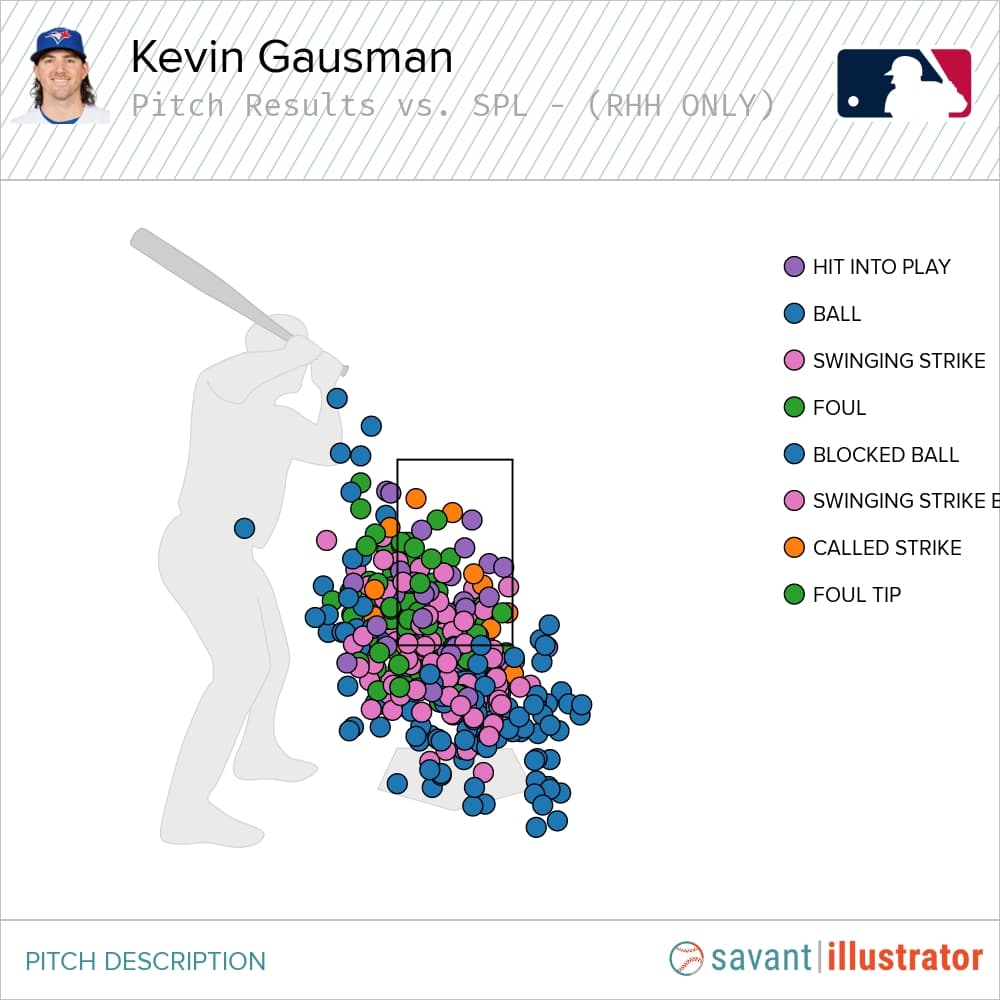

No off-speed pitch in baseball that’s been thrown at least 500 times has been chased as often as Gausy’s splitter. It’s running a chase rate of 39.7 percent, 2.6 percent better than Pablo Lopez’s second place changeup. He’s also throwing it out of the zone more than any other pitch with the above conditions. It’s only inside the strike zone 26.4 percent of the time it’s thrown., and it’s only called a strike at a rate of 3.8 percent. Both of these marks are very easily the lowest among not just all off-speed pitches, but all pitches in general. What makes this splitter so tough to hit though, is the disparity between it and Gausman’s 4SFB. That pitch is thrown inside the zone MORE than any other pitch in baseball. Let’s look at an overlay of the two pitches.

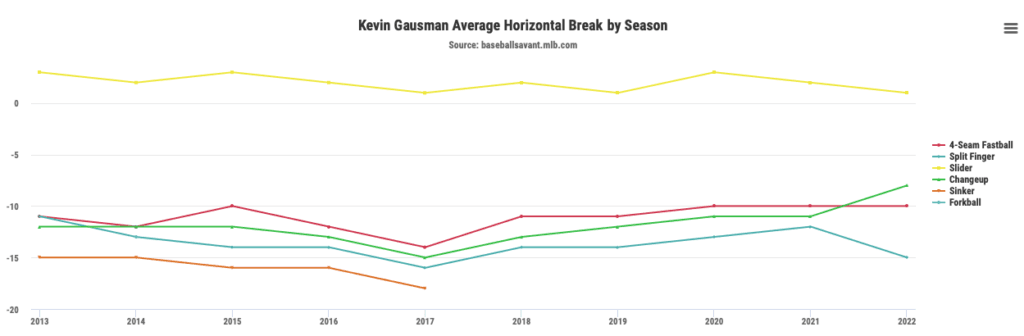

What makes the splitter so hard to hit isn’t even necessarily horizontal movement. Both basically move in the same direction, as you can see by this graph.

The inherent vertical movement of the splitter isn’t actually exceptional either. It only drops 0.1 inches more than the average MLB splitter. However, the splitter drops 20 inches more than the four-seamer does. That’s what makes it difficult to hit. Both pitches are starting in very similar spots, then one drops so far off the table that it’s untouchable, while the other one is nearly down the middle. This is exactly what happens in the Marcus Semien video. The fastball induced a very bad, very late swing, and the splitter induced a whiff. What’s interesting though, is that this juxtaposition between the two pitches makes the splitter good, but it actually makes the fastball bad. Why is that?

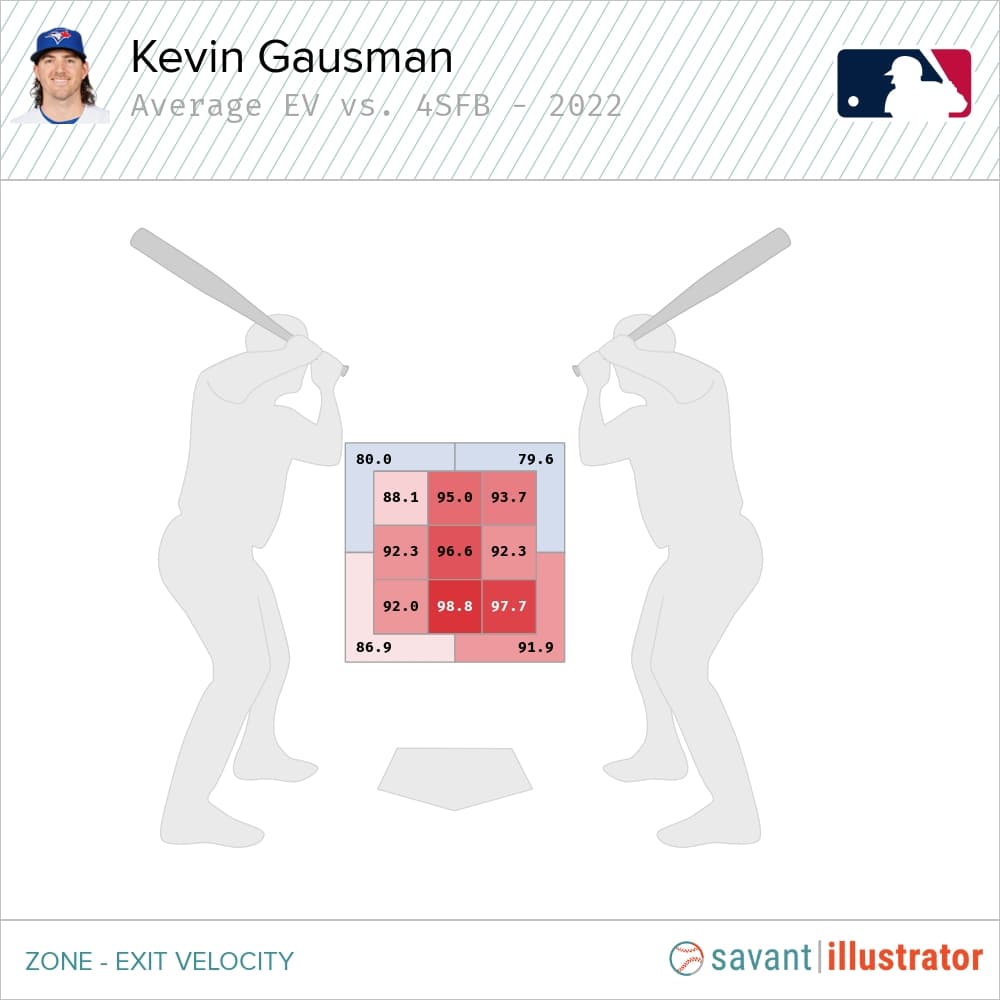

Gausman’s fastball gets hit very hard, very often.

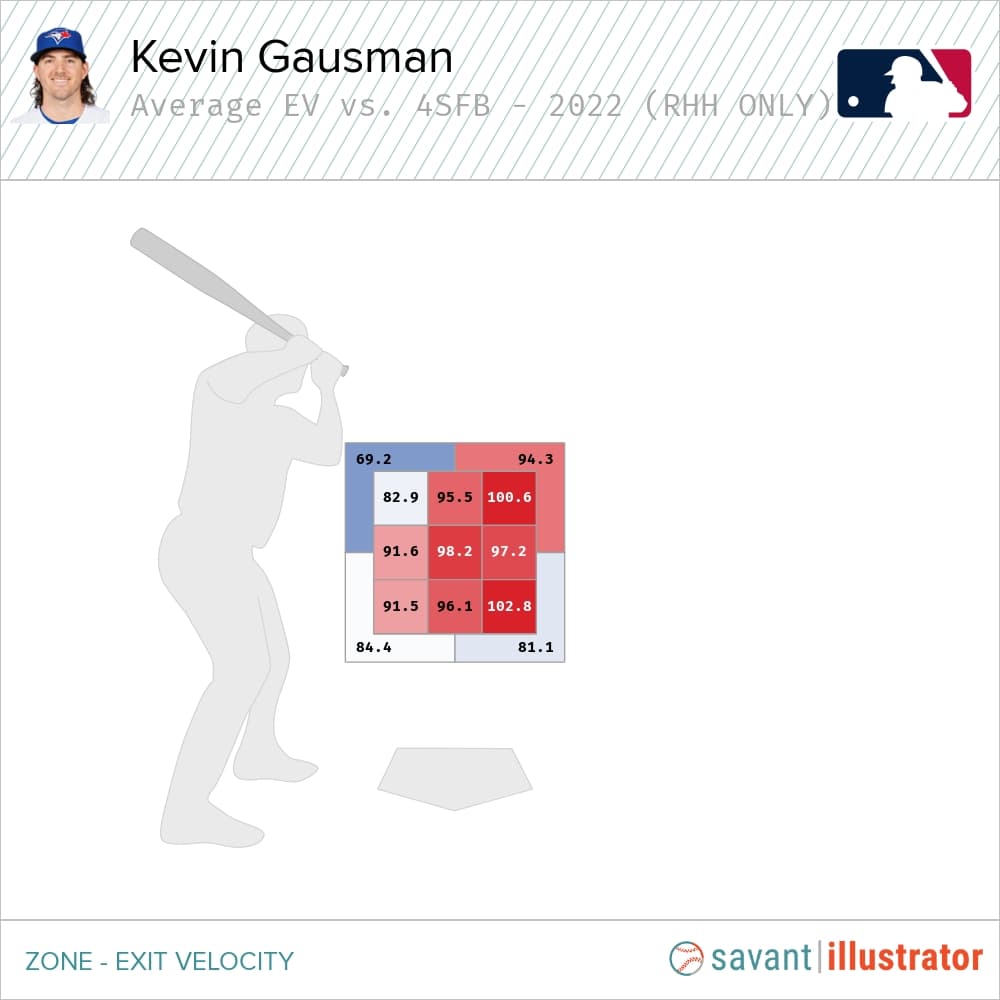

As we see here, it basically gets crushed if he puts it anywhere but up. When you filter down and look at the same data dependent on batter-handedness, you see that up and in is the only spot that the fastballs don’t get crushed. They still get hit hard when they’re thrown up and away. For example, let’s use the more prevalent RHH to discuss the issue with Gausman’s fastball. Here’s the exact same chart I just showed you, but this time, it’s righties only.

Gausman’s fastball gets hit hard by righties basically no matter where it is in the zone, but especially when it’s away. So then why is he throwing it in the zone more than any other pitch in baseball, as we mentioned before? Because if he didn’t, it would allow hitters to completely rule out one of his best two pitches. If he wasn’t a pitcher that threw in the zone often, the batter can pick whichever pitch they believe they can hit hard, and wait for Gausman to give it to them. This is because of the fact that they’ll be prepared not to chase, and Gausman can’t just walk everyone. However, his splitter is ineffective when thrown inside the zone, so he has to overcompensate by throwing the fastball for strikes.

As this chart shows, the more Gausman goes down and in, the more swinging strikes he gets. The more he comes into the zone, the more pitches that opponents are able to make contact on. Occasionally, he’ll get a called strike, but that has more to do with the fact that hitters aren’t conditioned to see the splitter in the zone, and take almost out of surprise. Getting CStr on a pitch designed to be a whiff machine won’t be a path to success. He has to throw splitters out of the zone, but he can’t throw everything out of the zone. So that’s why his fastball gets hit hard. As a matter of fact, among all 418 pitchers who have thrown at least 500 fastballs, Gausman’s allowing the 37th highest average exit velocity. Because he needs the fastball in order to maintain the effectiveness of the splitter, is there anything he can do? Well…yes.

Kevin Gausman used to throw a sinker. He hasn’t thrown a single one since 2017, but there was actually a point in time in which he used it more than his changeup. If he wants to take even another step towards becoming a Cy Young winner like Pedro Martinez before him, he needs to bring it back. Here’s why.

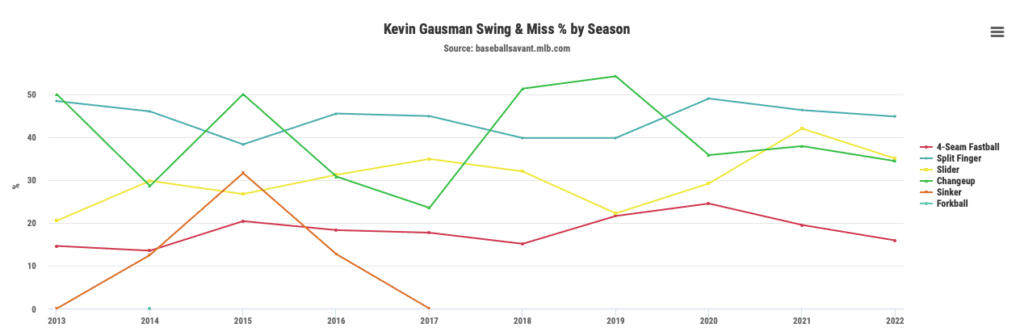

Small sample size be damned, we’re going to look at the data from sinker’s past. In 2015, Gausman got more swing and miss on his sinker than he ever did on the slider. In 2016, it became his worst swing and miss pitch, but that can be attributed to the fact that he threw it in the zone 30 percent more often.

That is why I’m proposing that Gausman brings back the sinker, as a fastball that he throws OUT of the strike zone. This can help him for plenty of different reasons. This season, Kevin’s longest period of struggles came when hitters wouldn’t chase the splitter, knowing that he had to throw them a fastball inside the zone eventually.

However, adding another fastball that he can put outside of the zone can help negate that problem, especially with the late movement that sinkers have, hitters wouldn’t be able to simply identify a fastball out of the hand and know it was coming down the middle. The sinker has a horizontal break that’s most similar to Gausman’s splitter, but is at a drastically different speed and doesn’t drop as much. Because he’d be enabling himself to try and generate chases with that pitch, it would be even easier for a batter to conflate a sinker with a splitter. They move the same, until the splitter drops and hits the dirt. Even if the hitter guessed correctly, it’s hard to hit pitches hard when they’re out of the zone. Here’s the graph showing the horizontal run on Gausman’s pitches. As you can see, he actually had more run on the sinker than the splitter in previous years.

Plus, you can’t sit movement, because that’s when he’ll break out the four-seamer in the zone. Similarly to how the fastball allows the splitter to excel despite being a mediocre pitch in and of itself, the sinker would allow the fastball to be more effective, even if it’s not all that good of a pitch either.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to see Gausman making this change, as Pete Walker’s an incredibly four-seam-oriented pitching coach, and would likely not encourage Gausman to throw a sinker even five percent of the time. He wouldn’t be throwing the sinker even close to as often as his FF/SPL, or even the slider, and so it’s basically a zero-risk change. It’s an even lower risk when you consider the fact that Kevin’s slider has been his second worst pitch this year by wOBA, and the sinker would primarily be eating into the usage of that breaking ball, which isn’t even a great pitch. In fairness, it’s not as if Gausy’s been bad in 2022 and needs to make this change, it just might add a new dimension to his game, and allow a weakness to become a strength. We know how good Jose Berrios’s sinker has been in 2022, so let’s compare the movement of that pitch and Gausman’s when he used to throw it.

- Kevin Gausman SNK (2016) – 133 pitches, -16 inches of horizontal movement, 14 inches of drop

- Kevin Gausman 4SFB (2022) – 1055 pitches, -11 inches of horizontal movement, 13 inches of drop

- Jose Berrios SNK (2022) – 503 pitches, -17 inches of horizontal movement, 21 inches of drop

- Jose Berrios 4SFB (2022) – 629 pitches, -11 inches of horizontal movement, 17 inches of drop

*Note: ‘negative’ horizontal movement indicates that the pitch moves the arm side relative to the pitcher’s handedness.

The vertical movement really isn’t similar at all between Berrios and Gausman, but we can see the similarity in the horizontal movement on each pitch. Moreover, Berrios just has a bit of a lame duck four-seam fastball that gets hit hard like crazy, and so he supplements it with a sinker. Gausman’s in a very comparable situation, and so trying to make the same change might help him take that next step. Let’s finish with another Pedro comparison.

In 2018, Pedro Martinez was officially inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. However, he was not honoured at the ceremony until 2022. He had this to say about his stint in Canada…

“It’s hard to describe how passionate and supportive the fans were… I’m just as passionate about Montreal and Canada as I am about Boston and the Dominican Republic. It was a mutual respect and love and admiration for each other…I love everywhere I played, but Montreal was the safest and easiest going city I played for… I really enjoyed my time here in Canada.”

It’s still early days, but Kevin Gausman’s admiration for the country seems to match. After signing in Toronto, he and his wife began to play O’Canada for his daughter Sadie, who now counts the Canadian national anthem among her favourite songs. Gausman also spoke positively of Blue Jays fans and their ability to travel. He was “shocked we had so many Blue Jays fans [in Detroit]”, and had some great interactions with Canadian fans in Seattle, though he hilariously struggled to pronounce Saskatchewan.

Kevin Gausman loving the Canadian fans in town. “I already met some fans from Calgary and they were great. I can’t say the other name. It starts with an ’S.” But they were great, too.” #Bluejays

With any luck, and hopefully no more lockouts, Gausman will get the happy ending to his Canadian baseball career that Pedro Martinez never did, before joining him in the country’s baseball Hall of Fame.

All data via Fangraphs, Baseball Reference, Baseball Savant, and Alex Chamberlain’s Pitch Leaderboard. You can follow me on Twitter here, @6lXWAR. Thanks for reading!

POINTSBET IS LIVE IN ONTARIO

Breaking News

- Blue Jays officially announce Tyler Rogers signing, designate Justin Bruihl for assignment

- Future implications of Blue Jays’ 2026 payroll nearing historic $300 million

- Report: Yankees featured on Ketel Marte’s five-team no-trade clause

- 3 reasons why this offseason feels different for the Blue Jays

- Blue Jays: An analytical overview of reliever Tyler Rogers